I thought it would be an interesting experiment to see how the market has performed on the cusp of past recessions. Does the market know that a recession is about to happen? Does it behave differently just before a recession? Are there any early indicators of a recession we can deduce?

Lately, there has been a lot of talk about an upcoming US recession, in both the popular media as well as the blogosphere (e.g. see here or here). One major contributor to the rhetoric is the recent inversion between the short and long end of the yield curve. Yield curve inversion has been discussed as a reliable indicator of an upcoming recession.

The experiment

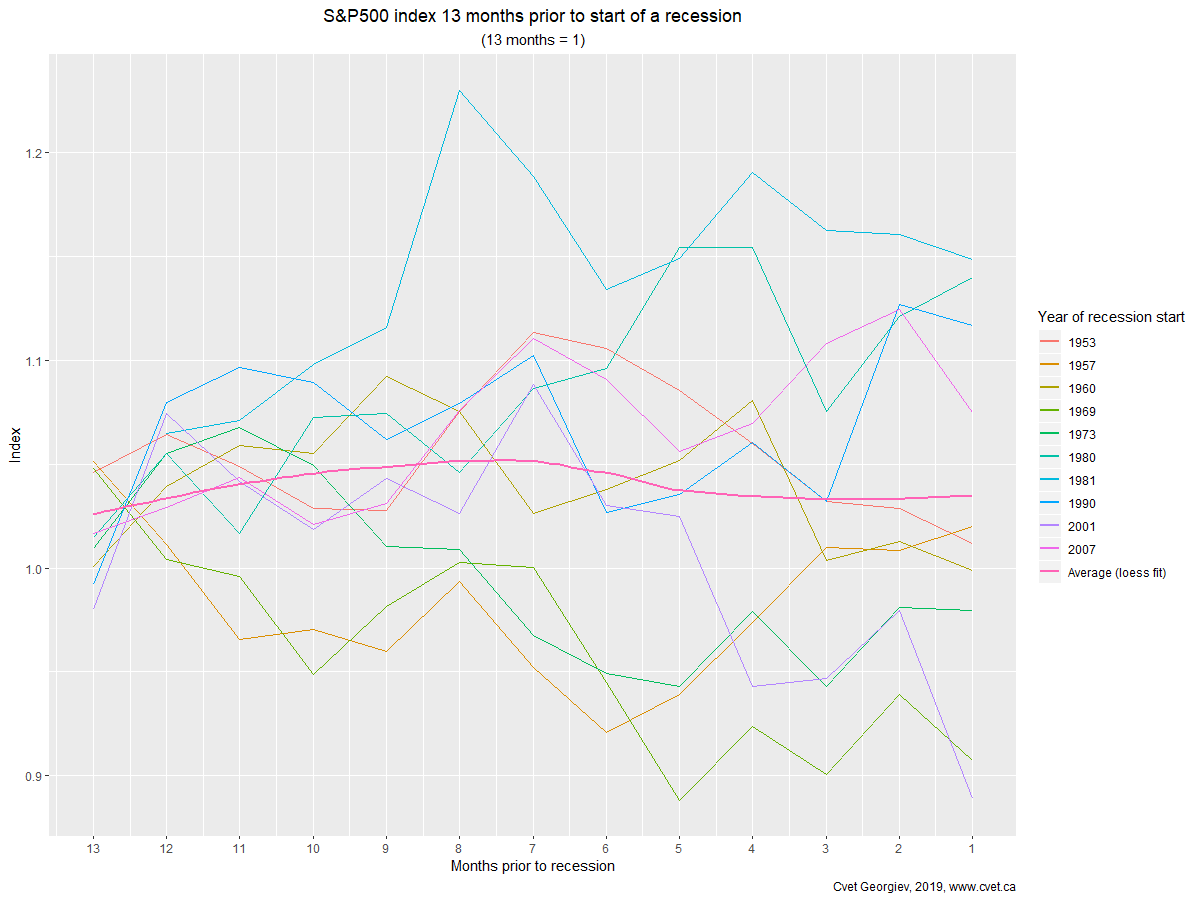

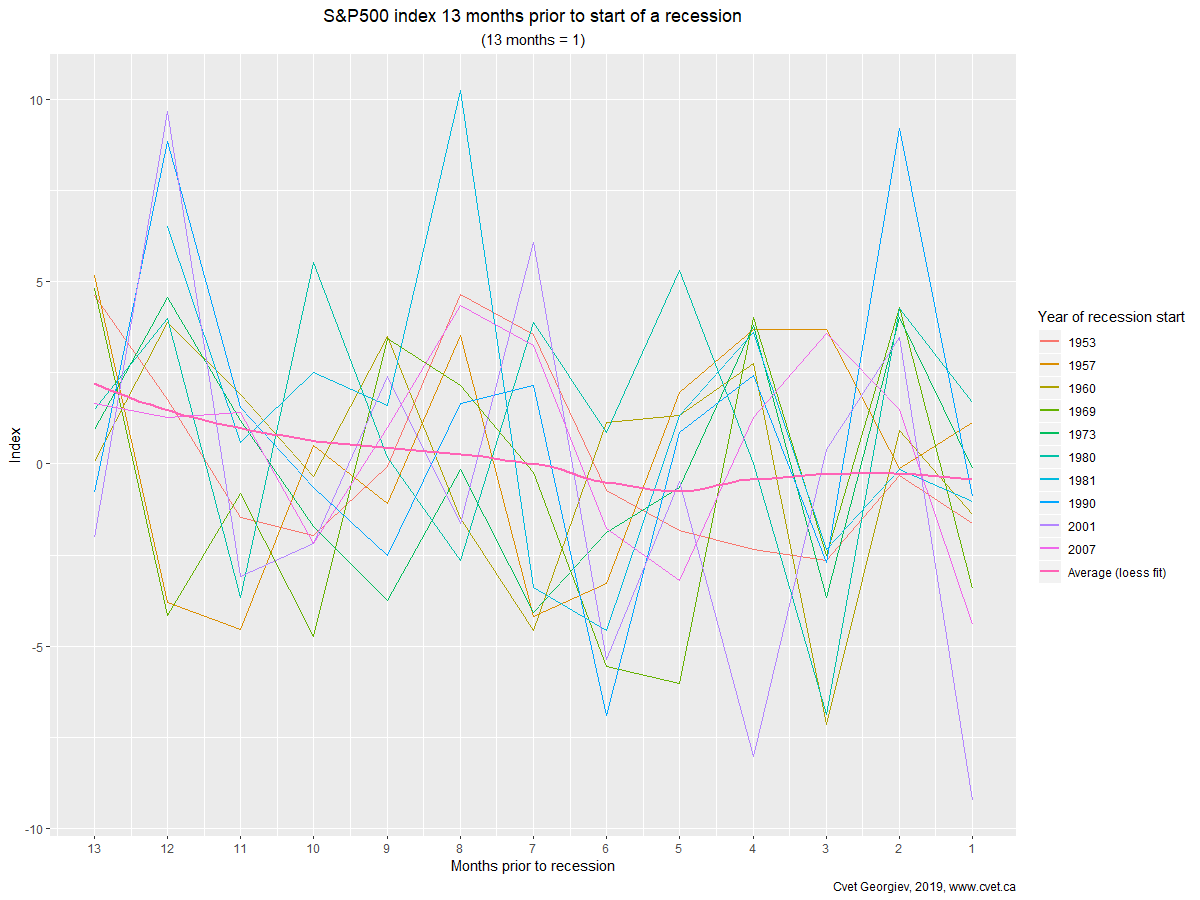

To visually see how the market has moved on a cusp of each recession, I plot the S&P 500 index returns over previous cycles just before a recession. This is not a statistical analysis, but I am curious to see if there any patterns that warrant further statistical study.

What does the data say?

Interestingly enough the data says what I expected it to say. The market has no idea it is about to go into a recession. Looking at the plots of the last 10 recessions, you see that the market is all over the place just before a recession (recession starts at t=0 or the rightmost part of the graph).

In some years the market is up about 15% up before a recession hits, notably 1981. In others, it is down 10% like in 1969 and 2001 (See Figure 1). There seem to be no discernable patterns you can use to gauge when a recession is coming even from a real-time indicator like the stock market.

Why is the yield curve used as an indicator of a recession?

The reasons given vary but it usually has to do with the normal operation of the financial sector. The main function of most banks is to provide loans to the private sector by borrowing money long-term and lending them short-term while charging a premium. With the inversion of the yield curve, the normal function of the financial sector is being disturbed as banks cannot borrow long-term and lend short since they would have to pay a premium. If this goes for long enough, a recession could originate from the financial sector.

Where does the data come from?

I use the NBER business cycle dating committee as the source of recession start and end dates. Data for “the market” is taken from Yahoo Finance. I use the S&P 500 index as an indicator of the market. It is large enough and covers broad sectors of the US economy that it should more or less represent the general market sentiment. There are better ways to get at the overall market (e.g. combining other US indices – Russell 2000, NASDAQ and Dow Jones) using Principal Component Analysis to get at the common movements across all US markets. For this simple exercise, using the S&P 500 will do the trick.

Recent Comments